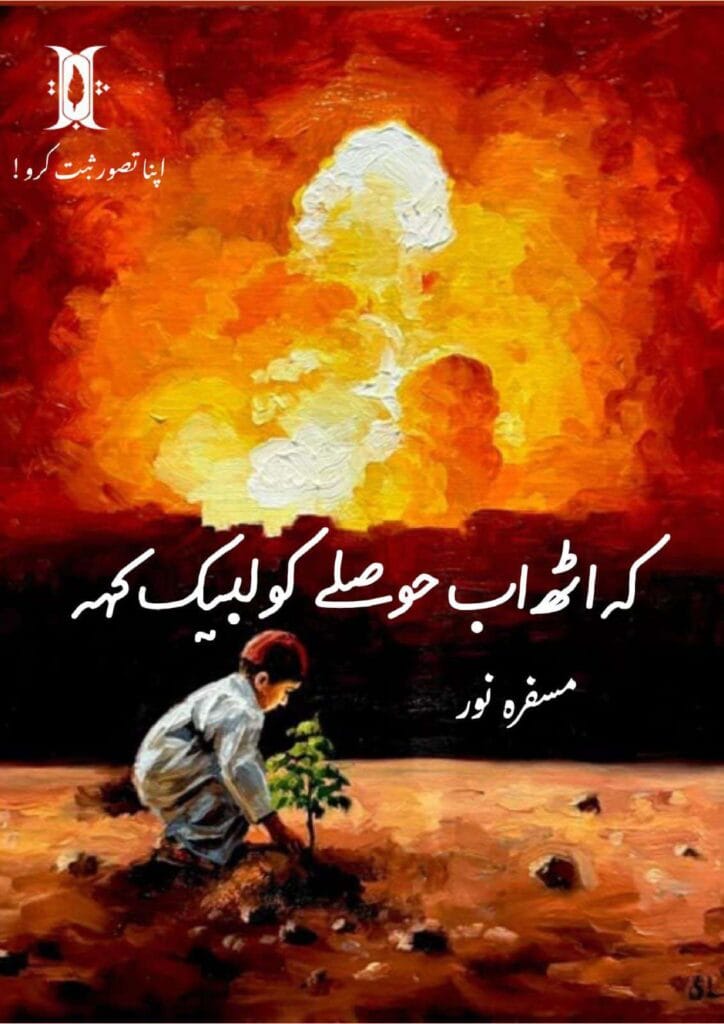

“کہ اٹھ اب حوصلے کو لبیک کہہ” دراصل میرے دل کی وہ آواز ہے جس کو میں نے لفظوں میں ڈھالنے کی پوری کوشش کی ہے۔ اس میں میں نے ایک طرف ان معصوم بچوں، ماؤں اور نوجوانوں کی بمباری کے سائے میں گزرتی زندگی کو قلمبند کیا ہے تو دوسری طرف امت مسلمہ کی غفلت، عیش و آرام اور بے حسی کو آئینہ دکھایا ہے۔ یہ تحریر دراصل ایک پکار ہے، ایک صدا ہے امتِ مسلمہ کے دلوں کو جھنجھوڑنے کے لیے، کہ وہ اپنے حصے کی قربانی دیں، اپنی زبان، قلم اور اعمال سے جہاد کریں اور مظلوم فلسطینیوں کے ساتھ کھڑے ہوں کیونکہ تاریخ گواہ ہے کہ “ہمتِ مرداں مددِ خدا” اور جب امت متحد ہو کر اپنے حصے کا فرض نبھاتی ہے تو آسمان سے نصرت اترتی ہے اور قلیل لشکر بھی غالب آجاتا ہے۔

“k uth ab hoslai ko labbayk keh” is not just an Urdu afsanah—it is a heartfelt cry, a literary mirror, and a social commentary-based narrative that dares to awaken the sleeping conscience of the Muslim Ummah. At its core, this afsana blends elements of resistance literature, spirituality, social awareness, and collective identity, while carrying undertones of romance-based longing, fairy tale-like hope, and even army-based valor.

The story paints two strikingly opposite worlds. On one side, it presents the raw and heart-wrenching reality of innocent children, mothers, and youth living under the shadows of bombardment, war, and oppression. Their tears, their silences, and their shattered dreams form the emotional backbone of this social commentary-based afsana. On the other side, it boldly exposes the heedlessness, luxury, and apathy of the wider Muslim community—those who are lost in comfort and indifference while their brothers and sisters suffer.

The afsana is designed as a wake-up call. It is not romance-based in the traditional “enemies to lovers” trope, but it carries the intensity of romantic suspense: the suspense of whether the Ummah will finally fall back in love with its duty, its faith, and its lost glory. It is almost fairy tale-like in its vision of unity and divine help, yet deeply army-based in its reminder that true strength lies in sacrifice, courage, and discipline.

Throughout the narrative, “k uth ab hoslai ko labbayk keh” weaves together multiple popular tropes and categories from Urdu literature. It feels like a social commentary-based mirror to today’s injustices, a romance-based longing for truth and sacrifice, a fairy tale of unity against oppression, a romantic suspense of faith versus fear, and even an allegory of enemies to lovers—where Muslims must shift from enmity with their own conscience to a love for their divine mission.

The afsana emphasizes that jihad is not merely about the battlefield but about using one’s pen, voice, and actions to resist oppression. It reflects army-based discipline in its call to action, yet it also holds the tenderness of romance-based themes by evoking compassion, solidarity, and emotional bonding with the oppressed. In its social commentary-based critique, it challenges materialism, ego, and heedlessness. In its fairy tale aspirations, it envisions a world where truth prevails and divine help descends upon the steadfast.

In the end, this afsana is more than a story—it is a pukar (a cry), a call to arms, and a reminder that history has always favored the courageous. It reminds us of the timeless truth: Himmat-e-mardan, madad-e-Khuda (when men rise with courage, God sends His help). Even a small, scattered group, if united and faithful, can overcome the greatest of oppressors.

Thus, “k uth ab hoslai ko labbayk keh” is not just literature. It is a movement, a social commentary-based afsanah that fuses the passion of romance-based emotions, the valor of army-based resolve, the dreamlike hope of a fairy tale, and the thrilling uncertainty of romantic suspense—all culminating in a powerful reminder that silence does not protect us, but courage transforms us.